Among my dozens of writing projects (the number alone is terrifying, because I can never possibly get them all done even without depression to contend with), there are four nonfiction books, all of them intended to be short enough to be monographs rather than comprehensive scholarly works. Two will be reactions to reading other nonfiction books (one is a reread, for me). The other two will be my personal takes on two filmmakers, both of whom are held to be "bad" by most people who are aware of their work.

This week, I'm telling you about Jess Franco: The Pulp Is Personal.

Jesús Franco Manera was a Spaniard who got involved in the Spanish film industry in his twenties, but started work as a director in his thirties. His first decade would be remarkable in any career — by the end of it, he had worked as a second unit director for Orson Welles, made a film praised quite highly by the elderly Fritz Lang, made the first Spanish-produced horror film, and worked with distinguished actors like Herbert Lom and Christopher Lee on multiple occasions.

But around 1970, Franco changed his career in several ways all at once. The rapid changes in the tenor of the times allowed him more and more to explore his erotic obsessions; and a successful experiment in making film with a small cast, virtually no crew, and in a limited timeframe set him on a path where he would often make eight feature films in a year, and in many years for the next two decades, ten or more films. He was not only directing, but often writing, producing, working the camera, acting in, scoring, and/or playing on the film score as a musician, and editing his films (the exact roles changing from film to film and as the fancy took him).

If you know me, this streak of independence obviously appeals to me. As one commentator put it, any time Franco had a choice between a big budget and creative freedom, he chose freedom. Whatever else there is to be said about the man and his work, I have to love that.

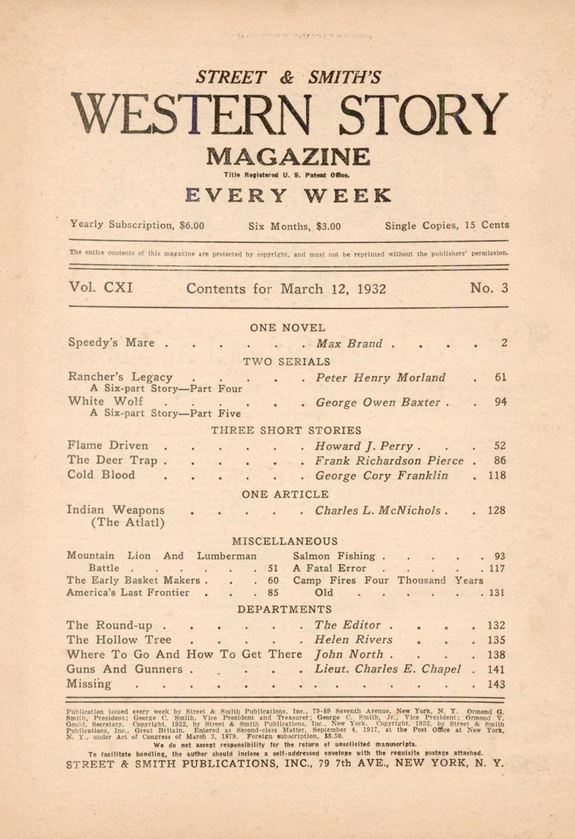

The angle I'm approaching his movies (the ones I have available to me, which is a limitation — my collection of twenty Blu Rays and thirteen DVDs comprises something like 15% of his IMDb filmography... but that gets complicated for reasons I go into in the book) from is one that I haven't seen any of the usual Franco experts explore as fully as I would like. Franco deliberately made "B" movies, and hated the idea of making "important" movies. Partly because of this inclination, he reveled in making movies that were informed by his knowledge of pulp fiction and comic books. Outside of the Marquis de Sade, the author he most frequently "adapted" was Edgar Wallace who, while technically not a pulp author, wrote books very much in the pulp mode. Franco also made a dozen or more noir-influenced private eye movies, and virtually all of film noir derives from American pulps. And while I can't document a direct influence, a few of his horror films have, for me, a taste of Lovecraftian influence. (Not a remote possibility: Lovecraft's work was published in French in the 1950s, and Franco was fluent in French and several other languages.)

If Raymond Chandler was, as Lawrence Block had it, a slumming angel, working in the pulps to try to create something good away from the eyes of the haughty intelligentsia, then Franco might be seen as a rancorous trickster, working in "crap" cinema so he could explore the ideas he wanted to, and work endless variations on them, without the critics deeming him important enough to bother with.

This book and the other director book (about which more later) scares me. I don't know how to write it. I have bits and pieces, and lots of ideas that tie into each other, but how to take what I feel in my head, and communicate it in comprehensible prose that doesn't repel everybody for its sheer pretentiousness, I have no idea.

(I might write about this on Locals at a later time, but the way my abstract thinking works is not like most people's thinking, as far as I can tell. Some people think in words, others think in pictures. My abstract thinking is closer to a Mondrian painting crossed with a lavalite lamp, and I have to take those ideas and connections, and find a way to make them clear to people outside of my head. Which is often not all that easy.)

There are also interesting parallels and contrasts between Franco and his hero, Orson Welles, which I'm not sure are within the purview of the book. Both worked outside "the system" for most of their lives. Both were perfectionsists, but in strikingly different ways. Both were intellectuals and highly intelligent men, who reveled in "low" art, and appreciated "high" art. (Welles held middlebrow art in disdain, and I'm unsure of Franco's position on it.) Both had side careers of a sort, Welles in magic and illusion, Franco in performing jazz.

But whether or not I include Welles as a compare-and-contrast figure in the book, Franco's insistence on doing "unimportant" movies in pulp genres like hard boiled private eye movies, monster movies, spy thrillers, and jungle adventure stories will be the main focus, and the way he obsessed over "trash" and cranked out interesting, deeply personal movies using "trash" as his toolset is one of my chief interests in him. (That and his continual maneuvering for artistic control and freedom.)